Day Zero / Ground Zero Cape Town

A Decolonial Walk along the Liesbeek River

This exhibition is best viewed full screen, on a large screen

DAY ZERO/ GROUND ZERO

Water in Cape Town became global news when, in 2018, it turned out that the city might actually run out of it.

On 30 January 2018, two New York Times journalists wrote of the situation: “It sounds like a Hollywood blockbuster. Dangerously low on water, Cape Town now faces ‘Day Zero’.”15 An unprecedentedly long drought, combined with overdevelopment, population growth, and climate change, were to blame for this potential apocalypse.

The daily newspaper The Independent reported that the city had

not seen anything like this since Jan van Riebeeck came ashore in April 1652 and took advantage of the bountiful streams and springs flowing off Table Mountain to plant gardens, fields and vineyards which provisioned the Dutch East India Company’s passing ships.6

Eventually, in 2018, winter rains offered relief, and Day Zero was deferred. Nevertheless, Cape Town’s “Anthropocene moment”, as Shepherd has coined it,24 offers incentives for thinking through the contested nature of water at the Cape of Good Hope. Particularly, the invitation is to think through the colonial heritage of water politics, in the light of the contemporary climate crisis.

Recently, writer Amitav Ghosh has

called for further investigation into the intimate link between imperial conquests and the exploitation of beings, species, and territories in former colonies such as South Africa.10 This story centers on the water course of the Liesbeek River, because its heritage encapsulates – in the words of the Goringhaicona Khoi Khoin Indigenous Traditional Council High Commissioner Tauriq Jenkins – the city’s “Ground Zero”, the place where colonial dispossession began.16

ACCESS TO WATER

Visser and myself are frequent visitors of Cape Town. Shepherd is a former resident, but now lives in Denmark. Since 2013, we have organized walking seminars on the Cape Peninsula, where this South African city is located.

In 2018, Cape Town had already experienced three years of draught. Until that moment, the three of us had never considered that the household supply of water of four million residents could actually be turned off. The prospect of Day Zero changed our assumptions fundamentally. It translated the impact of something as abstract as anthropogenic climate change to the level of people’s homes and everyday lives. We immediately sought to include this new reality in our research.

Cape Town is probably one of the most divided cities in the world. Unsurprisingly, the collapse of the water system affected Cape Town’s suburban middle classes differently than it did the urban poor. Long before the advent of Day Zero, the notion of water as a scarce commodity, and the need to queue for it daily, was all-too-familiar for dwellers of the city’s townships and informal settlements, who lack basic services.23

Day Zero drew our attention to how much of Cape Town was built on a race-based conflict over access to not only land but also water. Centuries of colonial conquest, slavery, and racist policies “systematically served the white population while marginalizing communities indigenous to the Cape, as well as other African peoples and the descendants of slaves originally brought from South-East Asia”.9

With this context in mind, we began our walk along the city’s most historically contested water sources.

DISPOSSESSION AND DEHUMANIZATION

Our Liesbeek River walk takes place

in 2019, some 30 years after the end

of apartheid, South Africa’s infamous political system of racial segregation and forced removal. We begin walking near the river’s two sources: the Window and Protea Streams. These streams can be found just above the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, a UNESCO World Heritage site as of 2004.

Kirstenbosch is closely associated with the most likely name-giver of the river, Jan van Riebeeck (1619–1677), a 17th- century commander of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Van Riebeeck arrived at the Cape in 1652, setting in motion the period of Dutch conquest. On encountering the Liesbeek River, he described is as “the loveliest of fresh rivers”. He considered the names “Varsche”, “Soete”, and “Amstel”, but eventually settled on the name “Liesbeek”.5

Only five years after the Dutch founded their settlement, the VOC issued the first permits to the so-called free burghers, freed VOC servants, to start farming along the Liesbeek. Van Riebeeck reserved for himself a farm called Boschheuvel, located in the Kirstenbosch area, at the southern end of the river.12 Kolb, who visited the Cape between 1706 and 1713, wrote about these farms roughly 60 years into the Dutch occupation:

The Company has here two very spacious, rich and beautiful gardens.

In one of [th]em stands, erected at the Company’s expens[e], a noble Pleasure House for the Governor, and near it a beautiful grove of oaks, call[e]d the [r]ound [b]ush from this Gardens takes its Name, being call[e]d the [Rondebosch] garden. The other garden which is at some distance from this, is call[e]d Newland, because but lately planted. Both these gardens are finely watered by the springs on the Table Hill and the Company draws from [th]em a very considerable revenue.14

In Kolb’s time, the Dutch did not yet occupy the Cape in an all-encompassing way. While the desire for domination was certainly setting the agenda, the free burghers remained mostly in the vicinity of farms such as Boschheuvel. Khoikhoi presence was strong outside these settlements.17

When walking through the contemporary botanical gardens there is little that reminds us of this colonial history and how it shaped the landscape.

This changes, however, when we exit Kirstenbosch and follow the streams across Rhodes Drive into what is now called the Boschenheuvel Arboretum and Protea Village. As Shepherd, Visser, and I walk through this site, which is on the edge of the leafy suburbs of Newlands and Bishopscourt, we discuss the history of Protea Village.

Between 1965 and 1968, Protea Village was declared “whites only” as a result of the apartheid government’s Group Areas Act (1950). Its inhabitants – 130 families – were classified colored and forcibly removed to the city’s far-flung townships. Almost all the buildings were destroyed. We traverse some of the old pathways amid the rubble from building material.1,12 Since its destruction, Protea Village has remained undeveloped, functioning as a kind of river park. During our walk we only encounter neighborhood folks walking their dogs.

We then discuss how it is most likely

that Protea Village was founded after the abolition of slavery in 1834 by formerly enslaved individuals. These were people who had been forced to work and live on farms like Van Riebeeck’s Boschheuvel in Newlands, as their 17th- and 18th-century ancestors had before them. Almost by definition, the beautiful pastoral landscape surrounding the Liesbeek River, described at length by Kolb, is intimately connected with a violent colonial history characterized by dehumanization and forced labor.

The past of Protea Village, then, is closely associated with “a politics of dispossession along the Liesbeek River Valley”. In the contemporary city, the community that once lived in this village, and that used the Liesbeek River as a source of clean drinking water, is still struggling to have their voices heard while reclaiming their homes.1,12 Researcher Anna Bohlin interviewed one former resident, who said:

We [as coloured people]26 don’t have places to say “I lived there”, “this is our culture”— we don’t have that. I want to go back, and tell my daughter, my grandchildren: “this is the river they played in, they used to do this in this area”. Something to look back at and share.1

RUMORS OF PARADISE

Our river walk near Protea Village is cut short by the electric fences belonging to luxurious villas in the area. We make a detour and eventually rejoin the river after it passes beneath Kirstenbosch Avenue. Here, we start a riverside walk through a beautifully maintained natural river landscape zone. This section of the river follows the southern border of the Newlands suburb. Along this route we discuss Kolb and his paradisiacal portrayal of the Cape and its rivers. Of Salt River, the confluence of the Liesbeek and Black rivers, for example, he wrote:

The source of the Salt River [is] on the summit of the table hill. In its course it receives several rivulets, and waters several fine estates, gardens and vineyards […]. Its water is as clear as crystal, and is esteem[e]d very wholesome.14

He also wrote:

I cannot help saying that if the waters at the Cape are not preferable to all others, for brightness, sweetness and salubrity, I believe there are none in the world that excel them. The European physicians at the Cape […] almost constantly advise their patients to drink the waters of

the country, instead of wine, brandy or another strong liquor, having found [them] very salutiferous in almost every case.14

Kolb was the first to introduce a scientific study of sorts about the Cape. And his portrayal of the Cape as a land of ease and plenty, where natural resources such as water were available in abundance, proved influential. Scientific explorers of the region after him, such as Nicolas- Louis de Lacaille (1713–1762), Francois le Vaillant (1753–1824), Robert Jacob Gordon (1743–1795), Carl Peter Thunberg (1743–1828), and John Barrow (1764– 1848), all studied his work. It is important to note here that Kolb’s work predates the Linnaean System of Nature.17 Nonetheless, he initiated at the Cape a way of capturing the natural world in a textual form. This would go on to become the way of knowing this particular landscape.

Kolb wrote about flora and fauna to point out “their curiosity, their medicinal potential, or their place in indigenous lifeways”.17 Through his writing, he intended to establish himself as a critical and systematic researcher in the tradition of the ars apodemica, a predecessor of the modern scientific method. Kolb’s description of the Cape’s landscape also fits into what has been called the physico-theological tradition: a way of writing about nature’s diversity that affirmed the Christian God’s greatness.

Kolb’s voyage to the Cape Colony was commissioned by the Prussian Geheimrat Von Krosigk. Since the 18th century, a string of rumors have accompanied his life and work. For example, he was thought by some to be a drunk who wrote his report on the Cape without ever having travelled outside of the confines of the VOC posts. A reluctance on Kolb’s part to travel to the Cape’s interior is understandable in the context of what historian Karel Schoeman refers to as the nervous desperation among VOC commanders about their colonial project. He suggests that, during the first decennia after 1652, the inhabitants of the VOC settlement were mainly focused on existential survival.20

Indeed, the South African novelist Andre Brink sees Kolb’s grand narratives as having an invented quality. Our historical knowledge of the early Cape landscape is at best suspect, he says, based not on facts about geological and climatological conditions but on text and imaginative reconstructions.4

In his 1993 historical novel On the Contrary, set in the early Cape colony, Brink’s main protagonist, an unnamed traveler, explorer, and scribe loosely based on the figure of Kolb, sighs:

For my own part I think that it does not little contribute to the discovery of truth in a history to know the temperament of the man who wrote it. It is not difficult to show that the constitution of a man frequently betrays him into falsehood. And yet the curious thing is that were it not for this latitude allowed the author, this permissibility of falsehood in the individual, no apprehension of the truth may be imaginable at all. It is only by allowing the possibility of the lie that we can grope […] towards what really happened, is happening, may yet happen.3

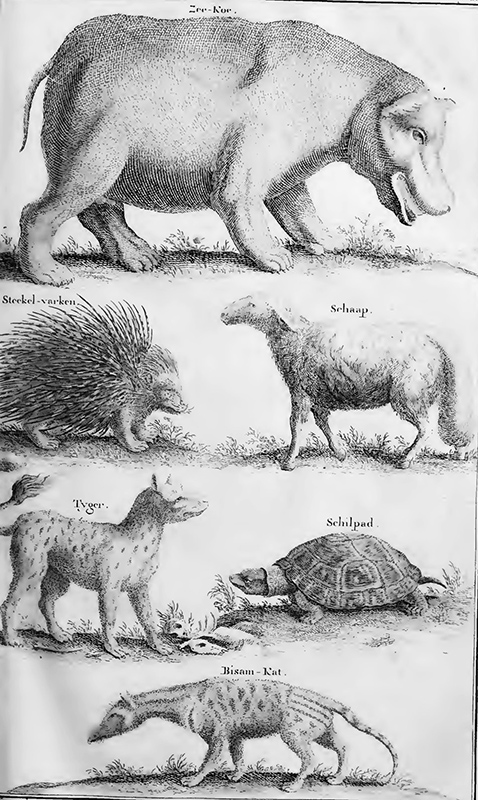

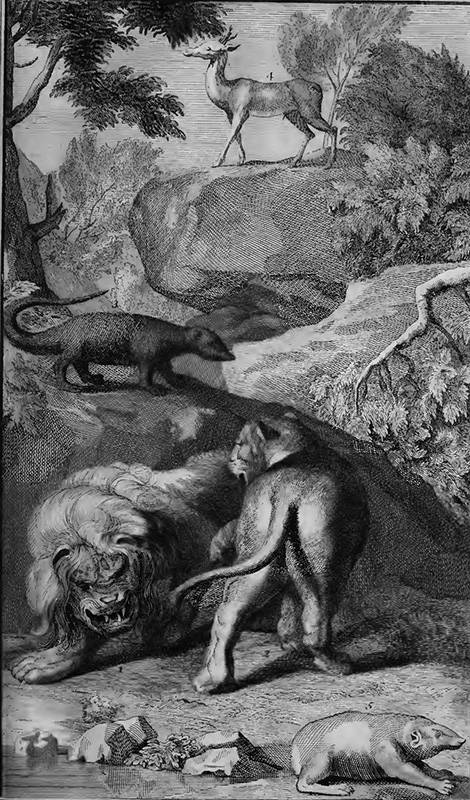

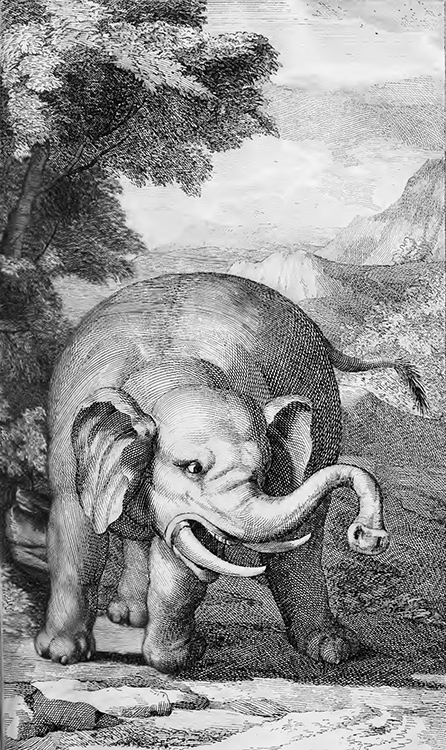

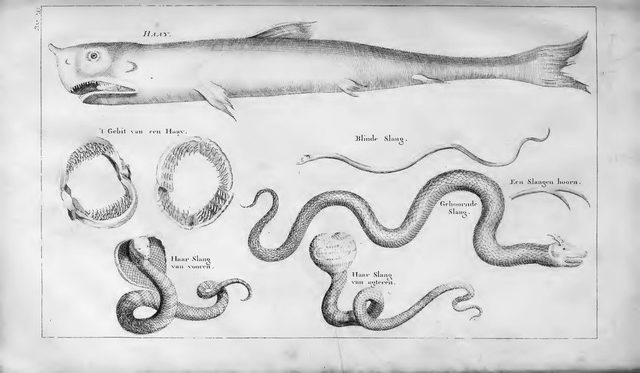

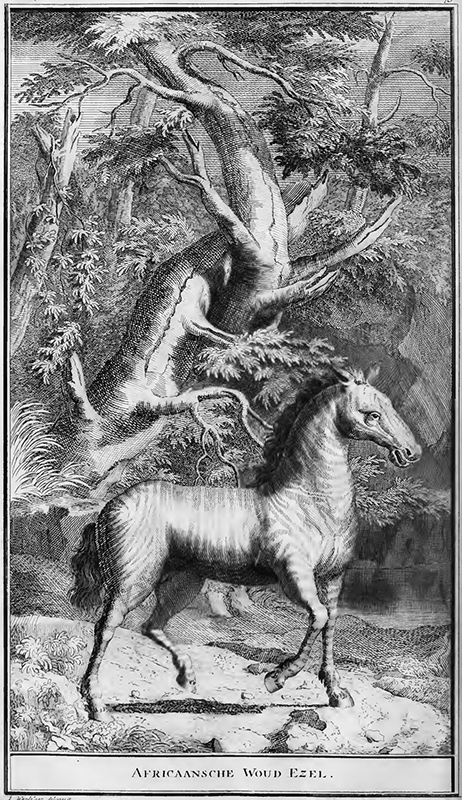

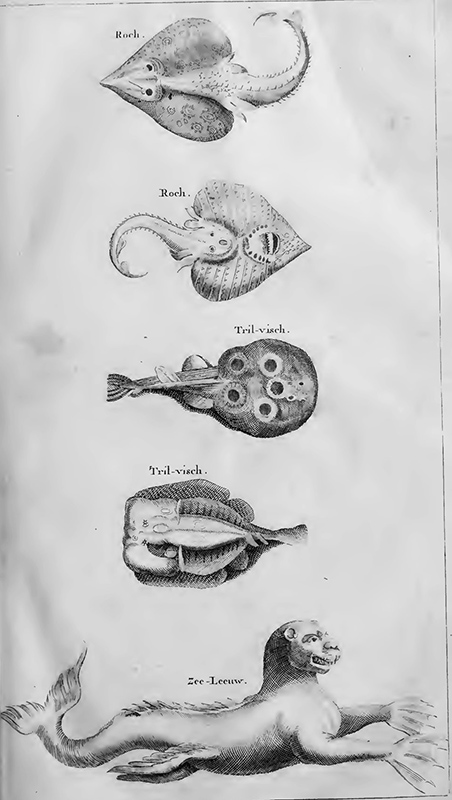

Shepherd, Visser, and I are intrigued by this idea that Kolb’s descriptions of the Liesbeek landscape were at least partly based on stories he heard. In his The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope (1731), depictions of wildlife abound. Kolb writes in great detail about antelope, zebra, wildebeest, warthogs, porcupines, elephants, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus, as well as predators such lions and leopards, often supplying illustrations of these animals. For instance, he has this

to say about the hippopotamus, or, as he calls it, the “sea-cow”:

A particular description of this creature I may give elsewhere. I shall only say of it here, that it is of a prodigious size, and makes frequent sallies up into the country to feed upon grass. This valley was formerly a great haunt of sea-cows. None, I believe, are seen or near it now a days. The great destruction the Eu- ropeans formerly made among [them] hereabout has driven [them] to other retreats.14

What does it mean that an influential piece of early-modern natural history writing about the Cape may have been grounded in make-believe and hearsay?

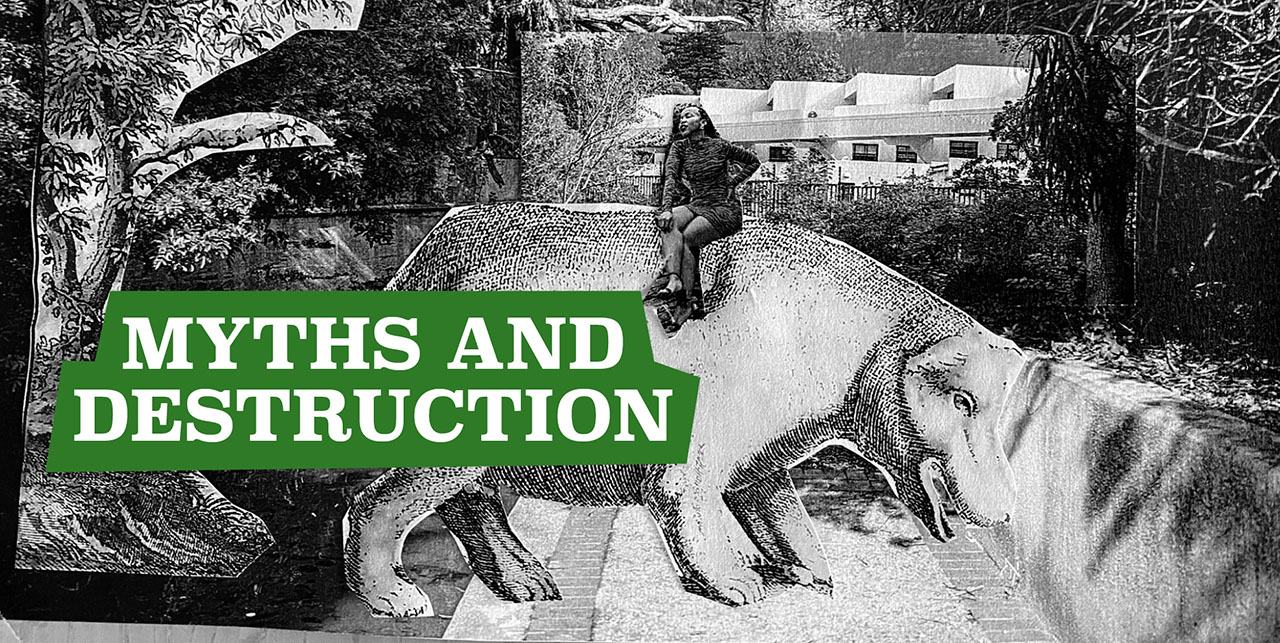

MYTHS AND DESTRUCTION

At the final section of the Newlands Riverside walk, the Liesbeek River becomes canalized, and after passing the M3 motorway near Paradise Park we lose the view of the river completely. As with modern-day Protea Village, this section of the river landscape has been privatized. We find ourselves suddenly among the leafy, suburban streets of southern Cape Town. We decide to walk to the four-star Vineyard Hotel, which is located on the river, to have coffee in its garden. The hotel is a typical European-style historical countryside mansion. The garden, which is located at the river’s edge, is designed to affirm its natural setting and is flanked by a small inner-city vineyard.

After a stroll through the peaceful garden, we discuss the image and idea of gardens at the Cape. Writer J.M. Coetzee, best known for his novels Disgrace and Waiting for Barbarians, has explored the mythology associated with the Cape garden landscape. He writes:

In its isolation from the great world, walled in by oceans and an unexplored northern wilderness, the colony of the Cape of Good Hope was indeed a kind of garden.7

Yet, while being imagined as a Garden of Eden or a New Amsterdam, the early Cape landscape also figured as a site for the potential degeneration of the white colonist into a native idle brute, like the so-called Hottentot. Coetzee writes about travel writers such as Kolb:

Like Joseph Conrad after them, [they] were apprehensive that Africa might turn out to be not a Garden but an anti- Garden, a garden ruled by the serpent, where wilderness takes root once again in men’s heart.7

Kolb definitely contributed to an emerging landscape discourse of Table Mountain and the Cape Peninsula as a place of bountiful streams and springs: the Cape as a paradisiacal garden. He wrote, for example, about the Cape’s river water:

With regard to color, the waters about the Cape, that have their sources on the summits of high hills, are mostly white and very clear: And as those waters mostly descend over pebbles and flint stones, and with great rapidity, they become, in their descent, still brighter, and are extremely sweet and wholesome.14

About the Drakenstein en Waveren regions, Kolb wrote:

This part is mountainous and stony, yet very fertile, producing everything, that is of the growth of the Cape countries, in great plenty. The air is serene and healthful, and the waters plentiful and good.14

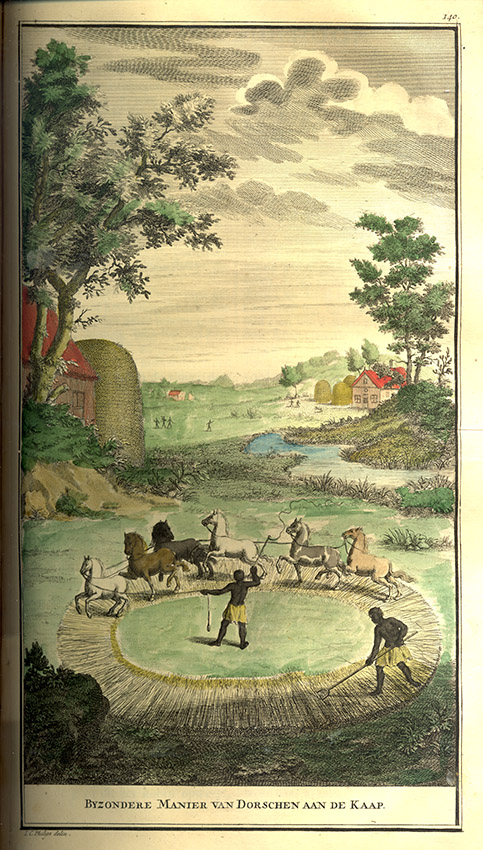

His depictions of Newlands and Rondebosch free burgher farm life in the Liesbeek Valley were contrasted with the agricultural activities of the Hottentots, while slave labor was hardly mentioned, adding to the racial undertones of the landscape myth.7

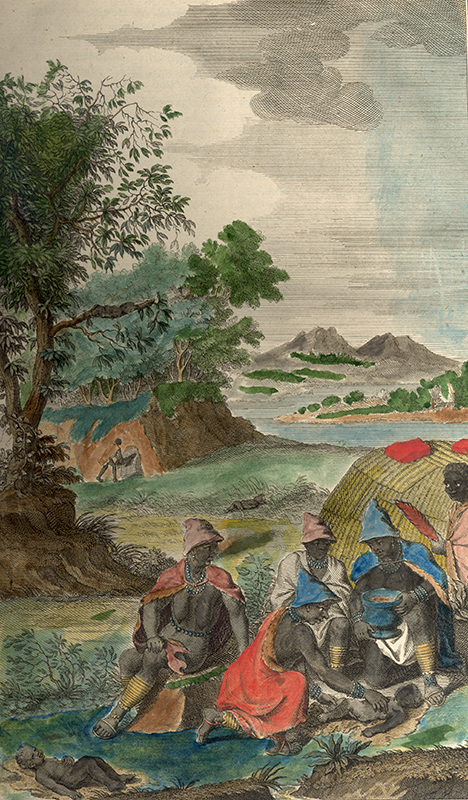

We then discuss one of the opening color drawings in the Dutch edition of Kolb’s book, an image by Balthazar Lakeman dated 1728, Amsterdam. It centrally depicts a half-naked black woman. In the French edition of the book the image has as a caption:

History prepares to write what she is taught by Experience […].17

In the background, Table Mountain

is visible, while a series of ships in

the foreground references maritime exploration. In addition, Lakeman draws a lion and an elephant, ivory objects, and individuals involved in map-making, as well as numerous figures depicted as indigenous. On a monumental structure, the insignia of the VOC is clearly marked.

This image nicely illustrates what linguist Mary Louise Pratt has referred as a “Eurocentered form of global or ‘planetary’ consciousness”.17 The landscape and its history become known to the male European observer—or, as Pratt writes, “he whose imperial eyes passively look out and possess”.17 Kolb’s books are a clear illustration of this kind of experiential natural history writing, and, in a sense, the carefully curated Vineyard Hotel shows how much these landscape myths still live on today.

At the same time, parallel to the description of paradisiacal farm life at the Cape, Kolb gave an account of how much destruction of nature had already taken place since the Europeans’ arrival. With regard to the wildlife on the Hottentot mountain range, he wrote:

This quarter was formerly a great haunt of wild beasts. The lion, the tiger, the leopard, the elephant, the rhinoceros, the elk, and every other sort of wild beast, seen in the Cape-countries. But, by powder and ball, they were quickly destroy[e]d or frighten[e]d into remote quarters. And now-a-days very rarely any wild beasts are seen here, besides deer, and goats of several kinds. When they are, they are quickly destroy[e]d or cha[she]d far away, and, by the fire and the noise of guns, deter[e]d from ever appearing there again.14

In a kind of environmental critique of the practices of Governor of the Cape Willem Adriaan van der Stel (1664–1733), he also said this about the mountainous area:

This quarter, the valleys and clefts of rocks in and about it, was provided with abundance of fine trees for building, and abundance of small wood for fuel, till Adrian van der Stel appear[e]d at the helm of the Cape government; who cut down and bestow[e]d the best of both sorts upon the castle and other sumptuous edifices he erected in this quarter, which is now but thinly provided with wood for either building or fuel.14

Sixty years into Dutch occupation, deforestation and big-game hunting had considerably changed the Cape’s landscape.

COLONIAL LANDSCAPES

We continue our walk and rejoin the canalized Liesbeek River near the Newlands Brewery on Boundary Road, which is also close to the border of the Newlands and Rondebosch suburbs. Kolb wrote about this part of the river:

Between those gardens [of Newlands and Rondebosch] stand[s] Lonwen’s famous brew-house, erected by Jacob Lonwen […]. The brew-house is plentifully supplied with water from the Springs on the Table Hill; which likewise waters all the circumjacent fields.14

Canalizing, piping, pumping, damming, and milling were by Kolb’s time in the Cape already clear characteristics of the colonial footprint on the landscape. He wrote, for example:

From [Table Mountain] falls a stream which turns a mill, belonging to the company, at the foot of the [mountain]. From thence, it passes through large pipes to the square between the fortress and the Cape Town, where through pumps, it plentifully supplies both the town and fortress with most delicious water for drinking.14

Kolb also wrote about the engineering works of governor Van der Stel near the settlement that would eventually become Stellenbosch:

Adrian van der Stel, who was a man

of admirable contrivance, made a very spacious and deep basin under the mountains, with such channels that the greatest part of the rain water from the mountains, on the side toward the quarter, fell into it[.] By this means he prevented, in the rainy seasons, the overflowing of his lands; and, by the same means, in the dry seasons, he supplied the river with water as he saw convenient. From this bason he cut a large channel to a whine-house he had in his quarter[.]14

Shepherd, Visser, and myself are still at the Newlands Brewery on Boundary Road. During the 2018 events preceding the expected arrival of Day Zero, SAB Brewers made its natural water spring available to the public. And the public came in great numbers with jerry cans.

We follow the canalized river through Rondebosch all the way to Riverside Mall, where we find a somewhat deteriorated section of the river, one that really resembles more of an urban sewer. It is at the mall that we lose sight of the river again. We can only rejoin it when it passes under the M57 motorway, or Liesbeek Parkway, which we proceed towards.

Here begins a more natural, park-like section of the river. This section continues until the River Club Golf Center, the Bird Sanctuary, and the Astronomical Observatory, also known as the Two Rivers Urban Park, where the Liesbeek River merges with the Black River.

We walk to the River Club Golf Center. This part of the river became a site of contestation in 2016, when a R4 billion (roughly €240 million) construction project that included residential, retail, and commercial areas was announced. The development would be financed and driven by Indigo Properties, best known for the regeneration of the Old Biscuit Mill in Salt River and the Woodstock Exchange in Woodstock, two rapidly gentrifying suburbs in Cape Town. These developers would have Jeff Bezos’ Amazon Group as its “anchor-tenant”.8,11,18

In 2018, in the direct aftermath of the Day Zero crisis, the Observatory Civic Association and the Two Rivers Urban Park Association opposed the proposed development. According to the local Cape Times newspaper, activists claimed the site as a 100-year-old flood plain that functioned as the cremation ground of the early Quena people. Indigenous community leader Jenkins was quoted as saying:

What is evident is that the historic landscape contained within the land between the Black and Liesbeek Rivers marks one of the most tangible and earliest historical frontiers that were to eventually herald the fragmentation of the Khoi Khoi nation.13

He went on:

The historical evidence is cohesive enough to confirm that the [Two Rivers Urban Park] forms part of the first frontier between the Dutch colonists and the Peninsula Khoi Khoi.13

The council asked that the provincial heritage authority, Heritage Western Cape, place a two-year moratorium on the development. An application was made to declare this part of the river a UNESCO heritage site. 25

One of the sources for this heritage claim was a 2015 heritage assessment report by the Archaeological Contract Office, which stated:

The Dutch identified the fertile valley of the Liesbeek Valley as prime agricultural land. The turning of the soil evoked the ire of the Khoikhoi as this was good grazing land used by them. The “fence” that was erected by the Dutch was a rather ad hoc barrier that involved using a mixture of natural features (deepening of the Liesbeek), a palisade fence in places and compelling the freeburgher farmers to erect barriers (thorn bushes, hedges, palisades) on the eastern side of their lands.19

According to this team of archeologists, the Liesbeek landscape marks “the beginning of the end” of Khoikhoi culture. Yet, in their view, it also “symbolises the process and patterns whereby the indigenous inhabitants of Africa, the New World, Asia and Australia-New Zeeland, succumbed to the tidal wave of colonial globalization”.19

While activists of the Salt River Heritage Society, the Observatory Civic Association, Oude Molen Eco Village, Iziko Museums, and the Goringhaicona Khoi Khoi Indigenous Traditional Council organized “walks of resistance”, the municipality appears to have given the development the go-ahead for mid-2021.18

GROUND ZERO

We stop our walk at the golf resort and consider ways of telling this Liesbeek river story differently. Referring to the River Club site and the Amazon-financed development, Jenkins said:

This is the place where the Khoikhoi and the San came in contact with the rest of the world. In 1657 the VOC decided in order to make profit to expropriate the land. Now centuries later the motives are still the same. It is the Ground Zero of contemporary South Africa.16

Indeed, archaeologists have found that the VOC Castle in current Cape Town was constructed on top of the debris

left by Stone Age people who lived in these lands for at least 600,000 years. Their presumed descendants—the San hunters-gatherers and Khoekhoe pastoral foragers—greeted the first European explorers on their way to the Indies long before the Dutch arrived.22

Archeologist Carmel Schrire writes that the basic VOC rules of exchange, whether enacted on board a ship, on the beach, in the courtyard of the Castle, in the stockyard of a farmstead, or in a wagon on the road, “were predicated on Company’s interests”. How, then, to move beyond a narrative informed by capital interests? How can we change our way of thinking about colonial travel and our way of knowing river landscapes?

A first point of departure could be reading Kolb’s The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope, first and foremost as evidence and trace of imperial exploitation at the Cape. Interest in capitalist extraction informed the ways in which colonial travel writers captured unknown worlds like the Cape in narrative form. Water sources such as the Liesbeek River necessarily functioned as a commodity in this way of knowing the landscape.

As a second step, we could recognize that the knowledge systems that emerged from the travel writing tradition obliterated local landscape knowledge. Here, we can perhaps start to think of making different connections across time. We can search for landscape imaginings that give an account of and stimulate forms of care, capturing something of the spirit of the place, and insinuating “its scent and character into interpretations of the past.”21 We might turn, for instance, to the narrative produced by Andre Brink in his novel The First Life of Adamastor, which contains scenes such as this:

High up on the rocky hill where they

had planted the cross I sat watching the brown egg coming slowly towards the land […]. It was still early dawn when I had gone up the hill with my goatskin bag filled with gifts for Heitsi-Eibib: a cal- abash of honey, an ostrich egg brought all the way from Camdebo, sour milk, goat fat, a small bag of buchu. Let those treacherous strangers do what they wish, I thought, I would rededicate this place to Heitsi-Eibib in the proper way.2

Finally, we could reflect on the transhistorical value of the walks of resistance organized by, among others, the Goringhaicona Khoi Khoin Indigenous Traditional Council at Two Rivers Urban Park.

ENDNOTES

1. Anna Bohlin, “Idioms of Return: Homecoming and Heritage in the Rebuilding of Protea Village, Cape Town”, African Studies, 70 (2011), 284–301.

2. Andre Brink, The First Life of Adamastor (London: Vintage, 1993).

3. ———, On the Contrary (London: Vintage, 1993).

4. ———, “Reinventing a Continent (Revisiting History in the Literature of the New South Africa: A Personal Testimony”, World Literature Today, 70 (1996), 17–23.

5. Cate Brown and Rembu Magoba, eds., Rivers and Wetlands of Cape Town: Caring for Our Rich Aquatic Heritage (Cape Town: Water Research Commission, 2009).

6. Dave Chambers, “Day Zero: The City of Cape Town Is About to Run out of Water – Its Main Reservoir Is Only 12% Full” (2018) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/day-zero-cape-town-drought-no-water-run-out-reservoir-supply-12-per-cent-16-april-south-africa-a8195011.html> [Accessed 12-6-2018].

7. J.M. Coetzee, White Writing: On the Culture of Letters in South Africa (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988).

8. Lindsay Dentlinger, “R4bn Redevelopment for CT’s River Club” (2016) <https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/r4bn-redevelopment-for-cts-river-club-2055324> [Accessed 27-6-2019].

9. Johan P. Enqvist and Gina Ziervogel, “Water Governance and Justice in Cape Town: An Overview”, WIREs Water (2019), 1–15.

10. Amitav Ghosh, The Great Deranngement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (London and Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017).

11. Mwangi Githahu, “Cheers and Jeers as River Club Development Gets Go-Ahead from City” (2021) <https://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/news/cheers-and-jeers-as-river-club-development-gets-go-ahead-from-city-bff436e3-3438-45c5-8d9a-1f67b12d7859> [Accessed 9-6-2021].

12. Tim Hart, “HIA for the Redevelopment of Erven 242 and 212 (Protea Village) Situated in Bishops Court, Cape Town (Assessment Conducted under Section 38 (8) of the National Heritage Resources Act (No. 25 of 1999) as Part of a Basic Assessment)”, prepared for Chand Environmental by Aco Associates Cc. Archaeology and Heritage Specialists (September 2019).

13. Lisa Isaacs, “Activists Slam Departments’ Appeal against Protecting Obs Land” (2018) <https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/activists-slam-departments-appeal-against-protecting-obs-land-17059736> [Accessed 28-6-2019].

14. Peter Kolb, The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope: Or, a Particular Account of the Several Nations of the Hottentots: Their Religion, Government, Laws, Customs, Ceremonies, and Opinions; Their Art of War, Professions, Language, Genius, &C. Together with a Short Account of the Dutch Settlement at the Cape, Written Originally in High German, by Peter Kolben, Done into English from the Original by Mr. Medley, Vol. 2 (London: W. Innys, 1731).

15. Norimitsu Onishi and Somini Sengupta, “Dangerously Low on Water, Cape Town Now Faces ‘Day Zero’” (2018) <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/30/world/africa/cape-town-day-zero.html> [Accessed 26-6-2018].

16. Niels Posthumus, “Precies Waar Ooit De Landroof Begon, Wil Kaapstad Nu Bouwn”, Trouw (2020).

17. M.L. Pratt, “Narrating the Anti-Conquest”, in Imperial Eyes: Travel Writings and Transculturation, ed. by M.L. Pratt (New York: Routledge, 1992).

18. Steven Robins and Matthew Wingfield, “Decolonizing Cape Town’s Rivers, on Foot?: ‘Walks of Resistance’ in the Empire of Amazon

at the Tip of Africa”, in Drift, Pause, Indirection: Walking as Embodied Research in Emergent Anthropocene Landscapes, ed. by Christian Ernsten and Nick Shepherd (New York: Routledge, forthcoming).

19. Liesbet Schietecatte and Tim Hart, “The First Frontier: An Assessment of the Pre-Colonial and Proto-Historical Significance of the Two Rivers Urban Park Site, Cape Town, Western Cape”, prepared for Atwell & Associates, ed. by ACO associates (Diep River: 2015).

20. Karel Schoeman, “‘Fort Ende Thuijn’: The Years of Dutch Colonization”, in Blank_ Architecture, Apartheid and After, ed. by Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavić (Rotterdam, Cape Town: Nai, 1998), pp. 33–39.

21. Carmel Schrire, “The Background of Archaeology of the VOC at the Cape”, in Historical Archaeology in South Africa: Material Culture of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape, ed. by Carmel Schrire (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, Inc, 2014).

22. “History, Architecture, and Archaeology of Selected VOC Sites at the Cape”, in Historical Archaeology in South Africa: Material Culture of the Dutch East India Company at the Cape, ed. by Carmel Schrire (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, Inc, 2014), pp. 29–64.

23. Nick Shepherd, “Cape Town’s ‘Day Zero’ Drought: Notes on a Future History of Urban Dwelling”, Space and Culture (2021), 1–19.

24. “Making Sense of ‘Day Zero’: Slow Catastrophes, Anthropocene Futures, and the Story of Cape Town’s Water Crisis”, Water 11 (2019), 1–19.

25. Unknown, “Declare Two Rivers Urban Park and Bo-Kaap Unesco Heritage Sites” (2018) <https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/news/declare- two-rivers-urban-park-and-bo-kaap-unesco- heritage-sites-18285121> [Accessed 4-6-21].

26. “Black” and “Coloured” were racial designations introduced by the apartheid regime. “Coloured” denotes an amalgamation of mestizo identities, including those held by descendants of Khoikhoi groups, people imported from the Dutch colonies, and other individuals; “Black” refers to those South Africans who are currently designated as Black/African, including groups as the Xhosas, the Zulus, and the Venda. “Black” and “Coloured” have remained widely used categories in contemporary South Africa. Although we consider notions of race bankrupt as analytical instruments, it is the general usage of these designations in the present context of South Africa that has led us to introduce them into this exhibition.

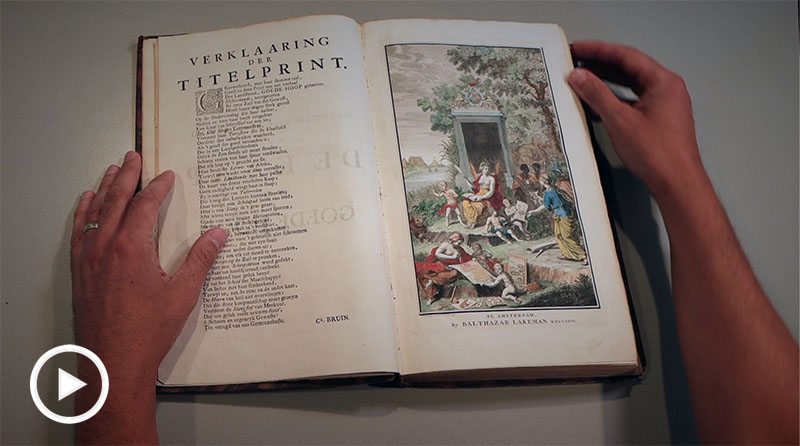

Kolb’s Naaukeurige en uitvoerige beschryving van de Kaap de Goede Hoop (1727), a Dutch translation of Caput Bonae Spei Hodiernum (1719)

This book is part of Maastricht University’s Special Collections and contains several hand-coloured images from the Khoisan peoples of South Africa. Here you see curator Odin Essers browsing through the first volume of this influential book. Video: Ilona Steege

How to take this walk along the Liesbeek river

For the best exhibition experience, please widen your screen. When scrolling down you can click on images that respond to your touch. Click here for a note on the authors.

This is a story about a river in Cape Town, South Africa: its colonial past and its Anthropocene future. It takes shapes as a 9 km–long walking conversation between photographer Dirk-Jan Visser and myself, historian Christian Ernsten, both from the Netherlands, and South African archaeologist Nick Shepherd.

As a kind of fourth companion, and historical interlocuter, we walk with Peter Kolb (1675–1726), the first known scientific explorer of the Cape of Good Hope – or, more precisely, with his writing. As such, we walk and read the Cape across time. Travel writing about the Cape of Good Hope is in many ways exemplary. As a result of scientific travel and the desire for inland colonial expansion to the Cape, it became a place where shifting relations between locals and newcomers played out with particular dramatic force.17

During the first decennia of the 17th century, Kolb mapped and described the Cape landscape, its rivers, and its people. While walking and reading his work, we confront the question: What would constitute a decolonial reading of Cape Town’s river landscape?

Peter Kolb (1675–1726)

Kolb was a traveler and explorer of the part of South Africa that is referred to as the “Cape of Good Hope.” In 1705, Kolb was appointed as the first official astronomer in the Cape, which has been occupied by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) since 1652. This portrait was done by Jacob Houbraken. Go to Longread

Rock paintings, Western Cape, South Africa

The Western Cape province, and especially its Cederberg region, has an incredibly rich archive of rock paintings. There are thousands of sites. The San, the first people of this region, revisited the many sites over thousands of years, leaving this accumulated tradition of painting. While the earliest art dates back to tens of thousands of years ago, the most recent paintings are from only a few hundred years ago—portraying settlers with guns on horses. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019.

Go to Longread

Cape Town and Table Mountain, South Africa

The city of Cape Town and the flat-topped mountain that forms its backdrop are located on the Cape Peninsula, or the Cape of Good Hope. This rough and wind-stricken terrain was used by Khoekhoen hunters and sheep herders before the VOC’s conquest in 1652. The Khoekhoen referred to the landscape as “Hoerikwaggo,” or “Mountain in the Sea.” Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019.

Go to Longread

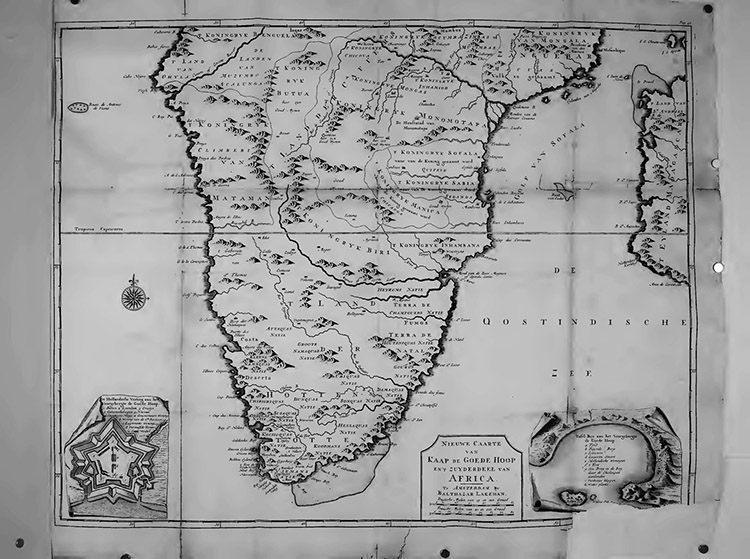

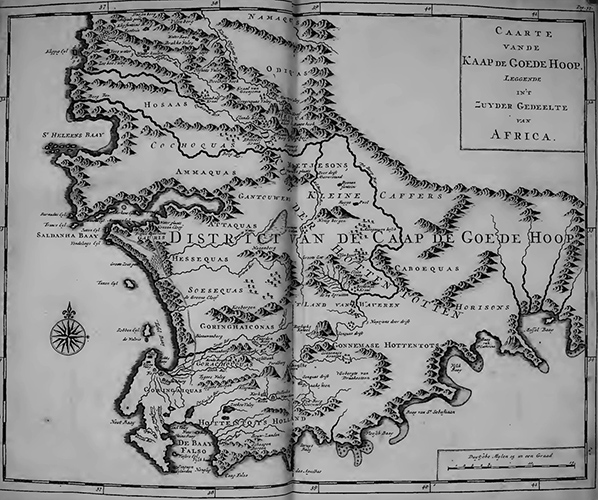

Map of the Cape of Good Hope

This map of the Cape of Good Hope is part of Peter Kolb’s book The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope, published in 1719. These drawings were done after Kolb returned to Europe. Go to Longread

We have “not seen anything like this since Jan van Riebeeck came ashore in April 1652 and took advantage of the bountiful streams and springs flowing off Table Mountain to plant gardens, fields and vineyards which provisioned the Dutch East India Company’s passing ships”

The Independent

Natural spring during Day Zero

The natural spring at Springway Road in the Newlands suburbs of Cape Town became a kind of common where people from all over the city came to collect water due the 2018 drought.

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2018. Go to Longread

“Gezigt van de Kaap de Goede Hoop”

This portrait of the Cape of Good Hope, or at least of the VOC settlement and Table Mountain, was done from the sea (instead of from the land). It is representative of the perspective of the colonial traveler. Kolb and his fellow travelers understood the landscape they arrived at as a “cape.” This particular locational term—a historical construct—still informs the regions contemporary identity. Go to Longread

Collecting water

A man at the Liesbeek River near the Two Rivers Urban Park collected drinking water.

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019. Go to Longread

Wildfires

Every year, the Cape Peninsula landscape—encompassing these fynbos fields—is struck by wildfires, resulting in part from a lack of rainfall.

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2018. Go to Longread

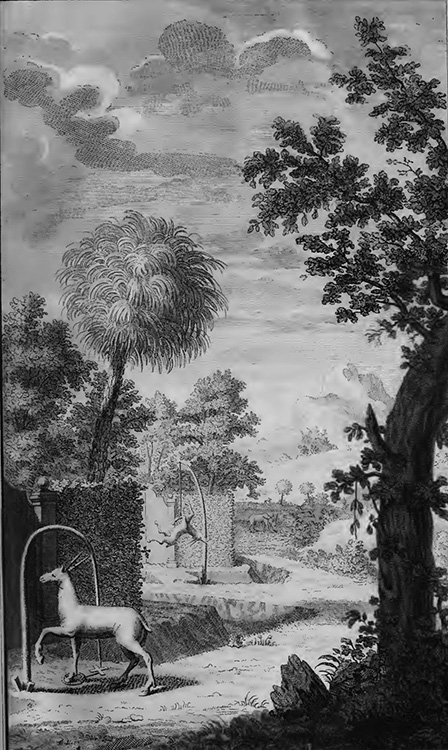

The Cape as a land of ease and plenty

In his book, Kolb portrayed the Cape as a land of ease and plenty, a place where natural resources such as water were available in abundance. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips based on the stories written by Kolb. Go to Longread

Ground Zero of contemporary South Africa

Goringhaicona Khoi Khoi Indigenous Traditional Council High Commissioner Tauriq Jenkins: “This is the place where the Khoikhoi and the San came in contact with the rest of the world. In 1657 the VOC decided in order to make profit to expropriate the land. Now centuries later the motives are still the same. It is the Ground Zero of contemporary South Africa.” Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019. Go to Longread

We [as coloured people]26 don’t have places to say ‘I lived there’, ‘this is our culture’ – we don’t have that. I want to go back, and tell my daughter, my grand-children: ‘this is the river they played in, they used to do this in this area’. Something to look back at and share …”

Former Protea Village resident

Boschheuvel

Located in the area that is currently Cape Town’s Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Jan van Riebeeck (1619–1677), the first commander of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Cape Town, founded his farm Boschheuvel. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019.

Go to Longread

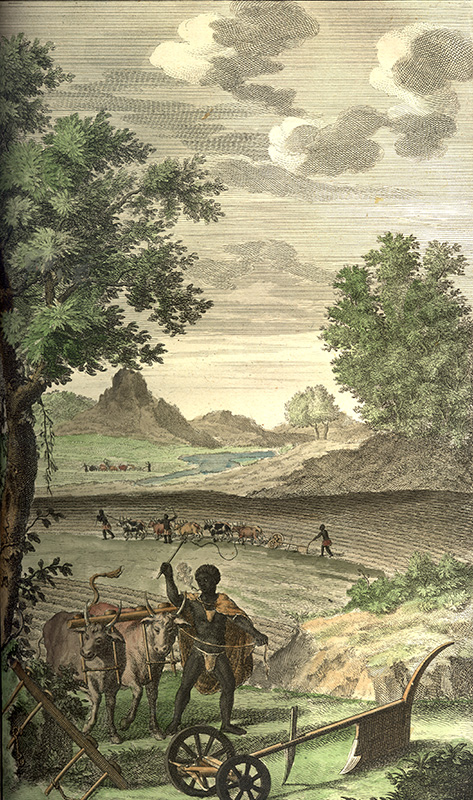

“De wyze van landbouwen aan de Kaap”

Agricultural practices at the Cape, according to Kolb. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips. Go to Longread

Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Cape Town

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

The spring of the Liesbeek River above the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Cape Town

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

“Africaansche woud ezel”

Kolb’s book contains a whole series of fantastical animals, such as this African wood donkey.

This drawing was done by J. Wandelaar. Go to Longread

The view of Newlands from above the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Cape Town

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

The source of the Salt River [is] on the summit of the ta- ble hill. In its course it receives several rivulets, and waters several fine estates, gardens and vineyards […]. Its water is as clear as crystal, and is esteem[e]d very wholesome.

Peter Kolb

European planetary consciousness

This drawing in Kolb’s book by Balthazar Lakeman portrays elements of European maritime exploration, such as a lion, ivory objects, and individuals involved in map-making, as well as figures depicted as indigenous Go to Longread

The Liesbeek River near Protea Village, Cape Town

Electric fences securing private property on the banks of the Liesbeek, near the ruins of Protea Village. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

“Op de wyze de Hottentotte de nieuw geboore kinderen handelen”

Kolb’s interpretation of how Khoenkhoen welcome a new child. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips.

Go to Longread

The Liesbeek River near Protea Village, Cape Town

This is where our river walk started, near the ruins of Protea Village and the lush suburbs of Newlands. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

“Zee leeuw”

Kolb’s book contains a whole series of fantastical animals. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips.

Go to Longread

In its isolation from the great world, walled in by oceans and an unexplored northern wilderness, the colony of the Cape of Good Hope was indeed a kind of garden.

J.M. Coetzee

This part is mountainous and stony, yet very fertile, producing everything, that is of the growth of the Cape countries, in great plenty. The air is serene and healthful, and the waters plentiful and good.

Peter Kolb

Near The Vineyard hotel, along the Liesbeek River Trail in Newlands, Cape Town

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

Two girls photographing each other

In the garden of The Vineyard hotel. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

River channel

The Liesbeek River in the Rondebosch suburb of Cape Town. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019

Go to Longread

Lush gardens

The garden of The Vineyard hotel, next to the Liesbeek River. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019

Go to Longread

“Manier van elantdieren vangen”

Kolb’s interpretation of how one captures elands at the Cape. Note the orderly landscape. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips. Go to Longread

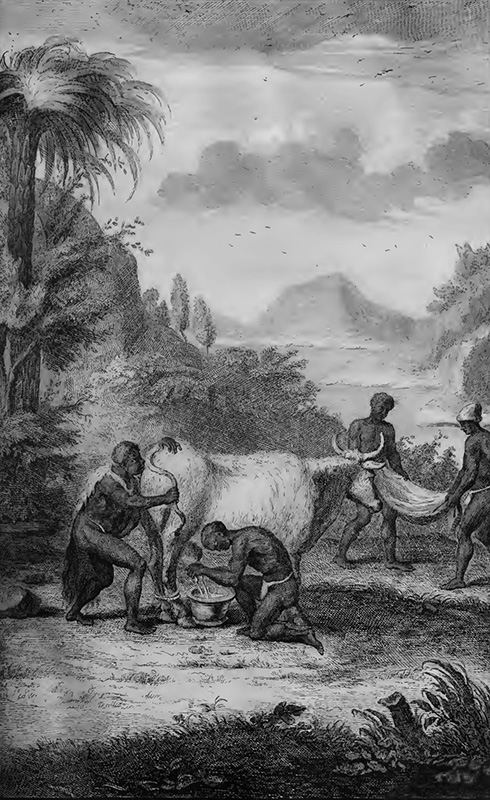

“Aardige manier van koejen te melken en boter te maken”

Kolb’s interpretation of how one milks cows and prepares butter at the Cape. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips. Go to Longread

Between those gardens [of Newlands and Rondenosch] stand[s] Lonwen’s famous brew-house, erected by Jacob Lonwen […]. The brew-house is plentifully supplied with water from the Springs on the Table Hill; which likewise water all the circumjacent fields.

Peter Kolb

Liesbeek River

The Liesbeek River near the Two Rivers Urban Park. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019

Go to Longread

Golf court at the River Club

The River Club, which is currently being developed by Amazon, is situated at the convergence of the Liesbeek and Black rivers. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

“De wyze van landbouwen aan de Kaap”

Agricultural practices at the Cape, according to Kolb. This drawing was done by I. C. Philips. Go to Longread

Rock paintings, Western Cape, South Africa

Much of the rock art in the Western Cape province is concerned with “trance,” an altered state of consciousness that is the central spiritual/religious experience of life for the San, the first people of the Western Cape. The San enter trance via a dance—intense repetitive movement. In trance they do all sorts of important work: healing the sick, traveling great distances to visit other groups, making rain by hunting a rain animal, and so on. The rock art is therefore not just about hunting and everyday life. It represents a way of being, based on a complex understanding of the world. Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2019 Go to Longread

High up on the rocky hill where they had planted the cross I sat watching the brown egg coming slowly towards the land until […]. It was still early dawn when I had gone up the hill with my goatskin bag filled with gifts for Heitsi-Eibib: a calabash of honey, an ostrich egg brought all the way from Camdebo, sour milk, goat fat, a small bag of buchu. Let those treacherous strangers do what they wish, I thought, I would rededicate this place to Heitsi-Eibib in the proper way.

Character in Andre Brink’s The first life of Adamastor

Sea view from the land

The beach north of Kommetjie, with Chapmans Peak in the background.

Photo by Dirk-Jan Visser, 2014

Go to Longread

The Cape from the Sea

The view of Cape Town and Table Mountain as one sails down south. From Kolb’s book The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope, published in 1719. Go to Longread

CREDITS

This is an online project for the Maastricht University Arts and Heritage Committee, realized in collaboration with students Lucinda Maitra, Pepijn Smits, Reanda de Beer, Zoe Zanello and Brendan Harris as well as Cecile Schulte of the Master Arts and Culture, specialization Arts and Heritage, Maastricht University.

Authorship of text, photography and graphic design vis-à-vis the usage of colonial archives is often source of contestation. Rightly so. In acknowledgement of our own privileged position, we hope this exhibition functions as a conservation piece about issues of authorship, historical injustice and the representation of colonials pasts and presents.

CHRISTIAN ERNSTEN

DIRK-JAN VISSER

CHRISTIAN ERNSTEN

DIRK-JAN VISSER

ERIK WONG

WEB DEVELOPMENT

IVO KRUCHTEN

ERIK WONG

IVO KRUCHTEN

For this exhibition a 1727 copy of Peter Kolb’s Naaukeurige en uitvoerige beschryving van de Kaap de Goede Hoop was used. This book is part of Maastricht University’s Special Collections and contains several hand-coloured images.

This project is made possible with the support of the Maastricht University Arts & Heritage Committee, Maastricht University Library, Maastricht Centre for Arts and Culture, Conservation and Heritage and the University Fund Limburg/SWOL.