Origins and importance of prize bindings

As Latin schools served as bastions of learning from the 16th to 19th centuries, scholars and educators sought innovative ways to inspire and motivate students in their pursuit of knowledge. It was within this context that the tradition of awarding prize bindings (called ‘prijsbanden’ in Dutch) for outstanding performance emerged, as a means to recognise and reward academic excellence. This tradition became popular in Europe and the UK.

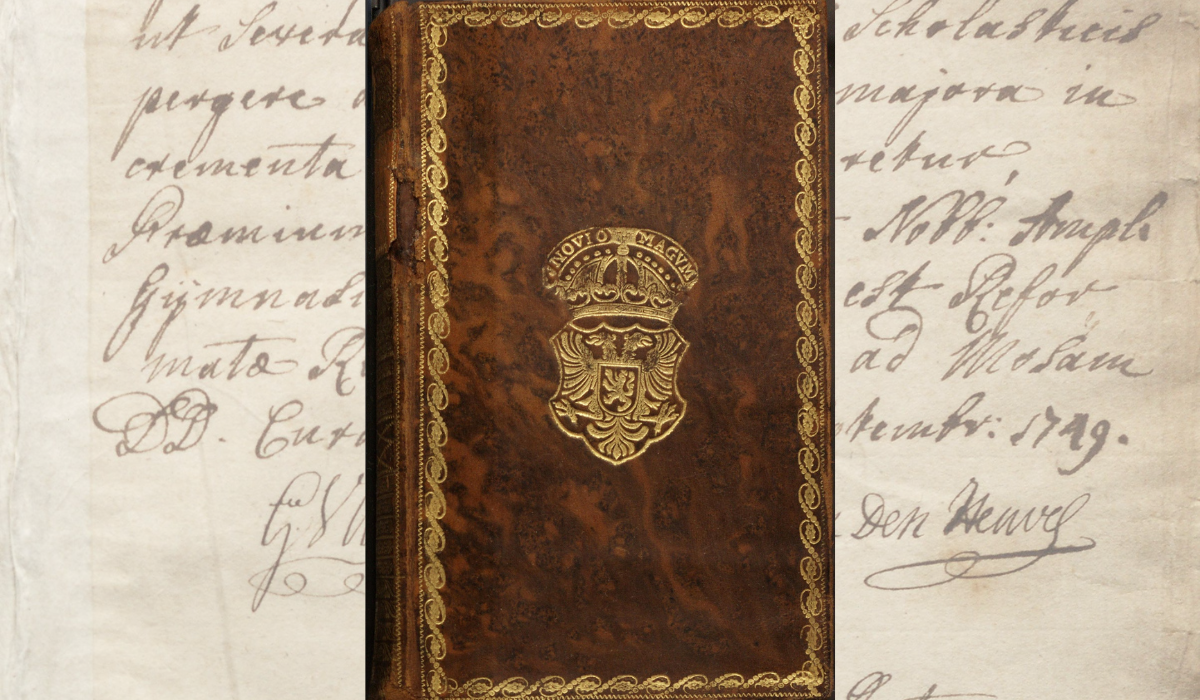

Right: A school prize binding from the Latin School of Amsterdam with original silk ties.

Distinctive features

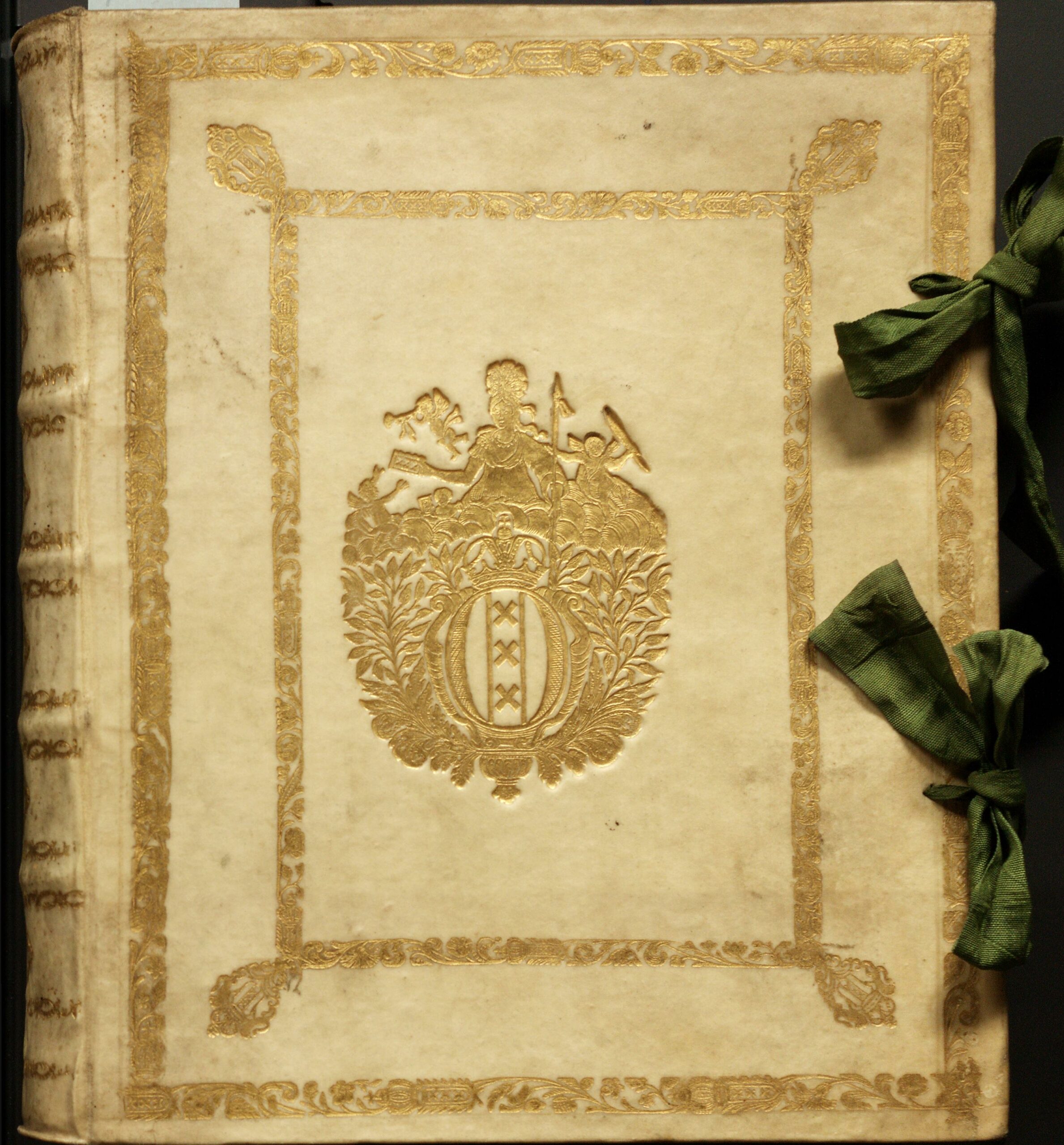

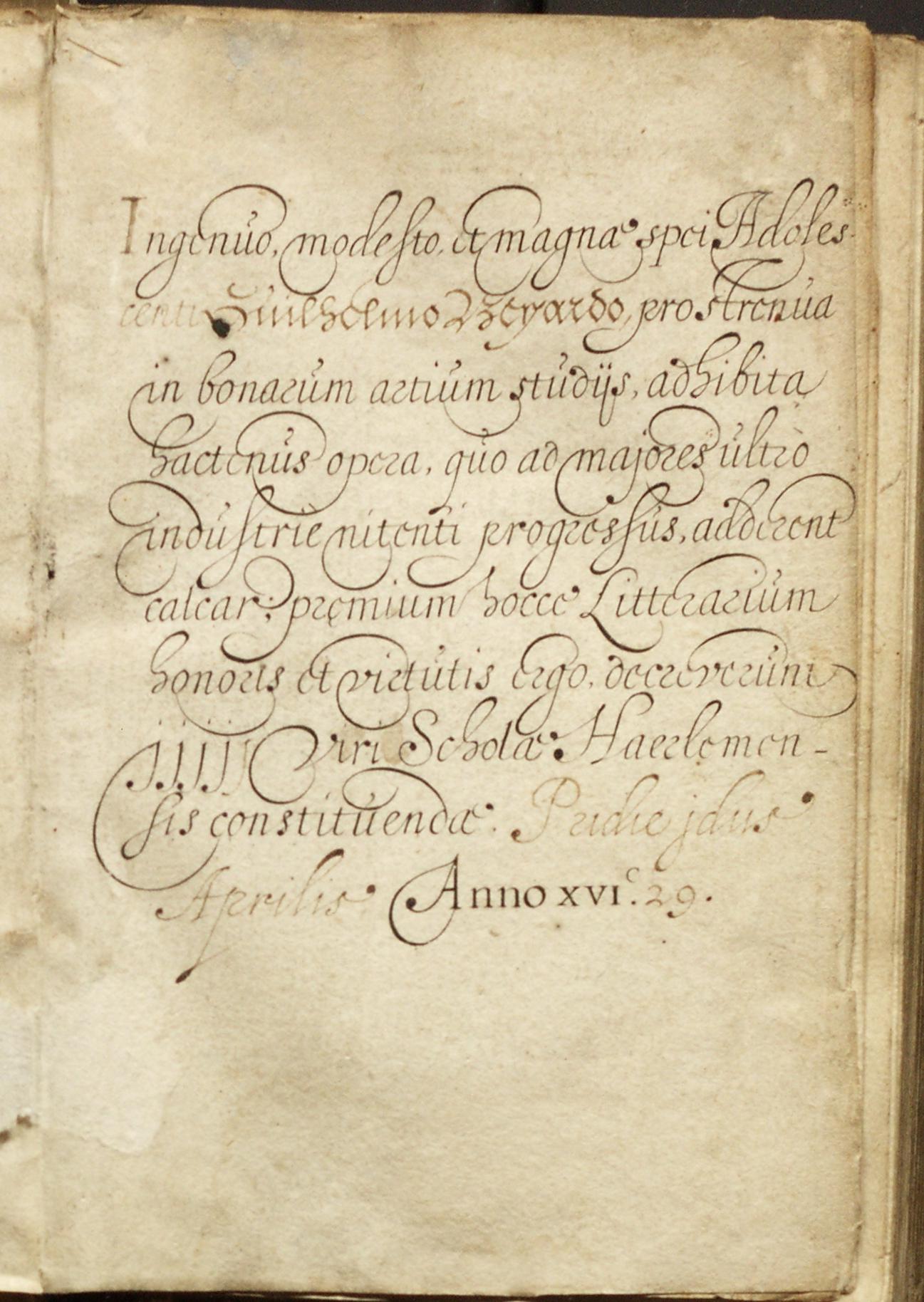

The oldest preserved prize binding housed in the Maastricht University’s (UM) Special Collections dates back to 1629 and originates from Haarlem. This particular volume contains the poems of Dutch writer and humanist Daniel Heyns and is very special as it is the second oldest prize binding in the Netherlands which is stamped with the city coat of arms. UM’s Special Collections boasts a total of 141 meticulously restored prize bindings.

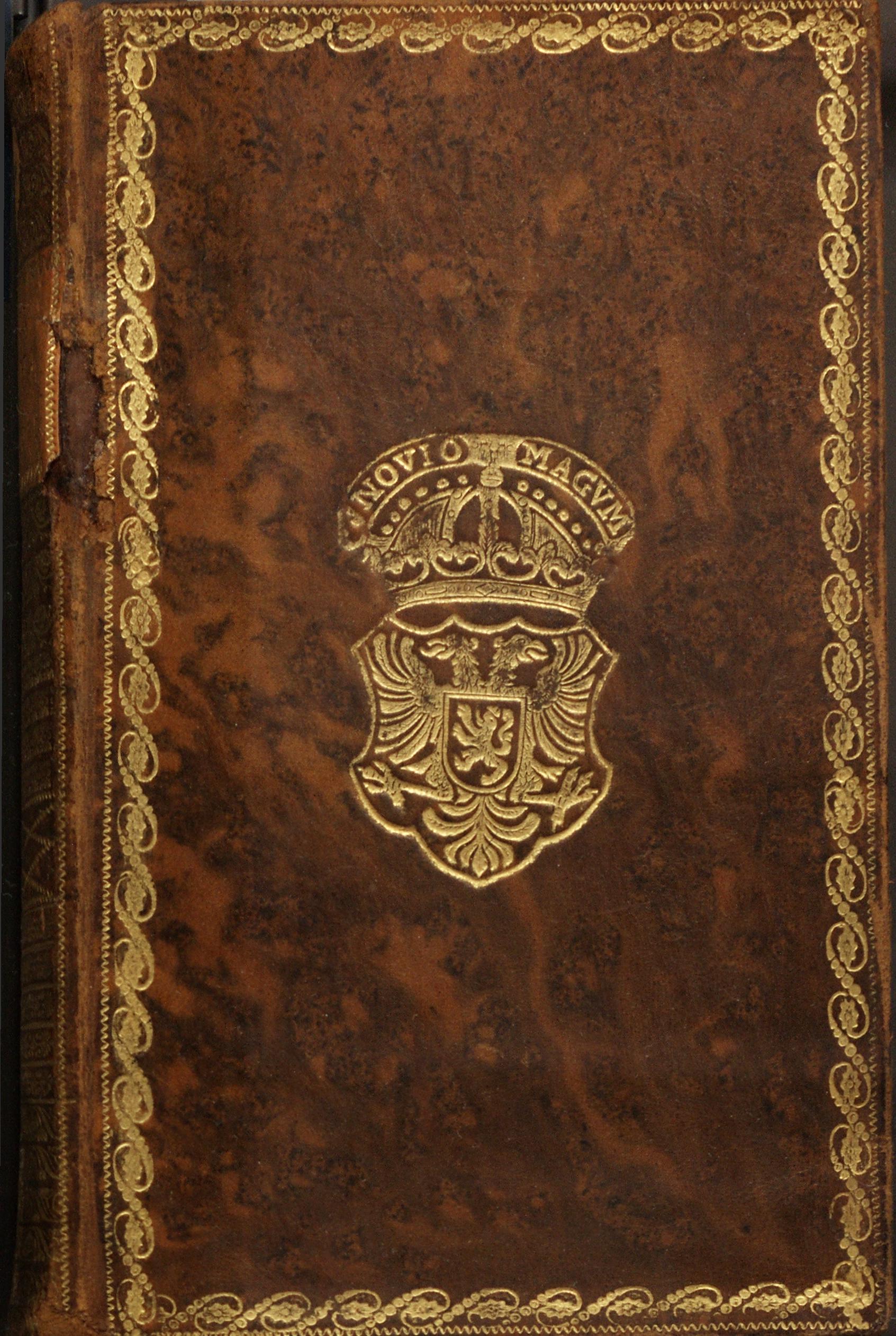

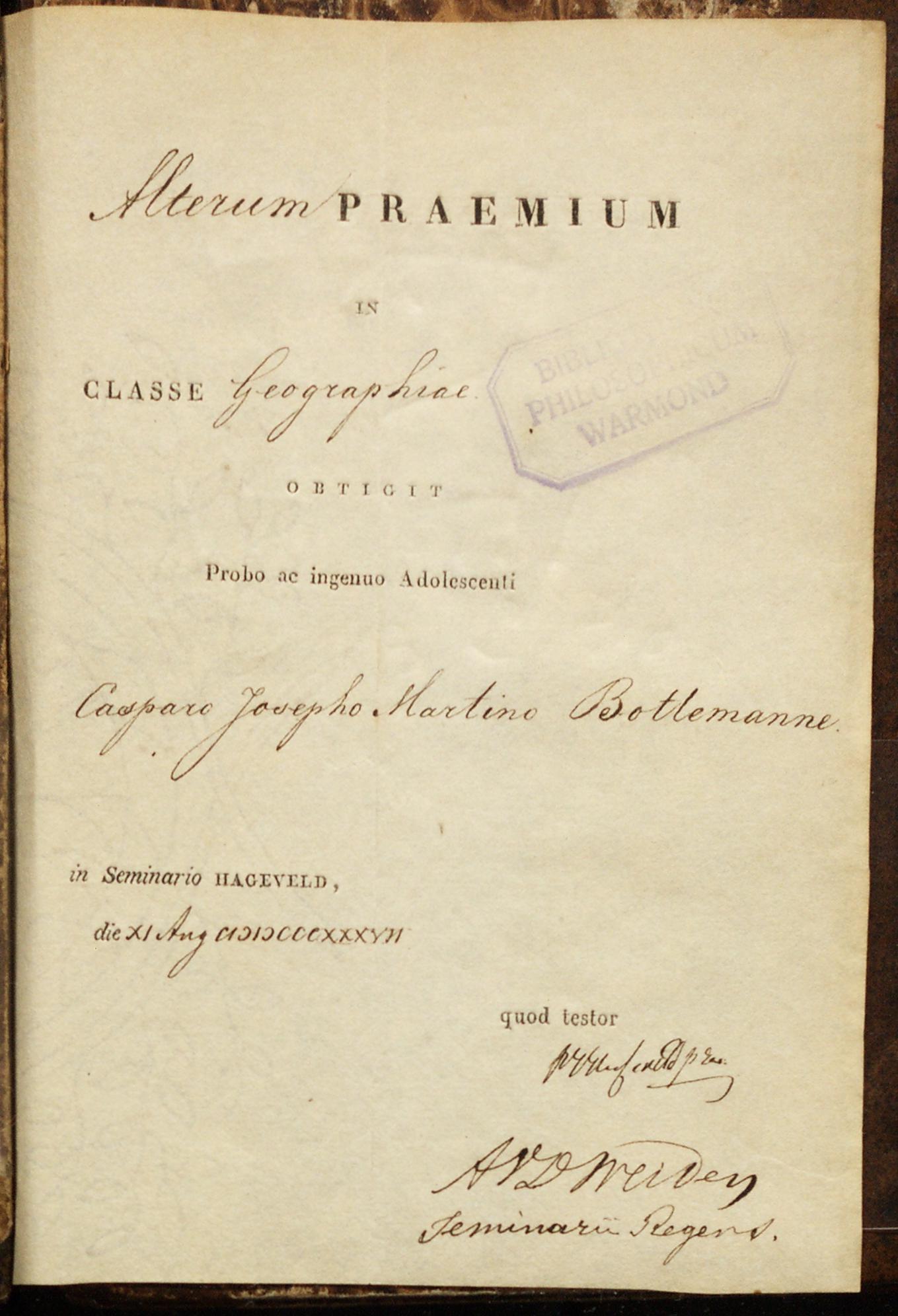

What sets a prize binding apart is its distinctive bookbinding of leather or parchment, often embellished with a gold leaf stamp indicating the sponsoring city or school. Typically, the book begins with a written or printed page displaying the signature of the school’s rector and a note explaining the reason for the reward.

The pedagogy of competition

At the heart of the prize binding tradition lies a pedagogy of competition, where students eagerly compete for academic accolades and recognition. Semester after semester, scholars awaited the public promotions with anticipation, where the best and brightest students were honoured with sought-after prize bindings. These ceremonies, often held in solemn reverence within the confines of the school or local church, served as a testament to the values of scholarship and intellectual achievement.

Left: Prize assignment for Gerard Willemszoon, a student of the Latin school in Haarlem, awarded on April 12, 1629.

Decline in the Netherlands

While the tradition of awarding prize bindings persisted in countries such as England, France, and Belgium, it gradually faded in the Netherlands in the mid-19th century. The transition from Latin schools to the gymnasium system in 1876 marked one reason for its decline, alongside pedagogical objections to competitive reward systems.

Insights from an expert

According to Dr Jan Spoelder, a classicist and expert on prize bindings, another reason for the decline was the belief that the practice of prize bindings could lead to negative behaviour such as jealousy and unhealthy competition among students. Furthermore, there was a shift in educational philosophy away from competition as a primary motivator.

Even today the debate continues about whether students should be rewarded for academic achievement or not. Some people are critical of the idea that students deserve encouragement and praise and see it as a form of “soft” education.

Right: Marbled leather binding with Nijmegen’s gold-stamped coat of arms.

Pride and prestige of prize bindings in the past

According to Spoelder, preserved prize bindings such as those in the UM’s Special Collections provide valuable perspectives into educational practices of the past. “It gives us insight into how education worked in the past, considering the upbringing of children, pedagogy, and how children were rewarded in those times.”

If your child was the winner of a prize binding, it was a significant source of pride for the parents. “In sketches from the time, one can see that parents really wanted their children to come home with a prize binding. For them it was a moment of great pride,” says Spoelder.

Left: Prize assignment for Caspar Joseph Martinus Bottemanne, who received a second prize for his achievements in the Geography class during his priest training at Seminar Hageveld on August 21, 1837.

UM’s Special Collections

UM’s Special Collections houses more than a hundred meticulously restored prize bindings. These books are accessible to students, researchers, and members of the public. Click here to plan a visit to the Special Collections depot at the Inner City Library in Maastricht.